MaDora Frey: Stargaze at Welch Gallery GSU

“MaDora Frey: Stargaze”

Curated by Cynthia Farnell

Welch Gallery at Georgia State University

September 24- November 13, 2020

Like so many others last March, when COVID-19 was new, my first and strongest desire was to spend time outdoors. It seemed my body was genetically programmed to seek the sanitizing powers of the sun and fresh air. Sculptor MaDora Frey was similarly compelled to reset the equilibrium by retreating outside. The result is Frey’s series of al fresco earthworks and gallery tableaux, called Stargaze, exhibited for the first time here at the Ernest G. Welch School of Art & Design Gallery at Georgia State University.

Frey grew up on a sylvan patch of land, in Conyers, Georgia, whose defining feature is a deep, spring-fed pond in the cavity of a former granite quarry. The gleaming surface of the water reflects the grass and surrounding ring of woods. To Frey, the pond is both a wound in the landscape and a womb that seduces with the promise of a refreshing swim. Speaking to the site’s meaning in her work, Frey says “ I didn’t think of it as man-made nature my entire life until recently. I just thought of it as nature.”

Not far from the Conyers pond is Davidson-Arabia Mountain Nature Preserve, a pair of granite outcroppings and former quarries where Frey spent time while growing up. The preserve is part of the Arabia Mountain National Heritage Area, a swath of 40,000 acres that encompasses past Creek and Cherokee communities, two predominately African-American communities - Flat Rock and Lithonia - and a web of quarries that, at one time, provided the raw material for the granite industry in Georgia.

Both sites function as community gathering places. The pond is home for Frey’s extended family and is the focal point for their shared history. Arabia Mountain serves a similar purpose for the general public who are seeking an experience there by hiking, biking, or sitting and watching the sunset. The common thread is the restorative communion with nature.

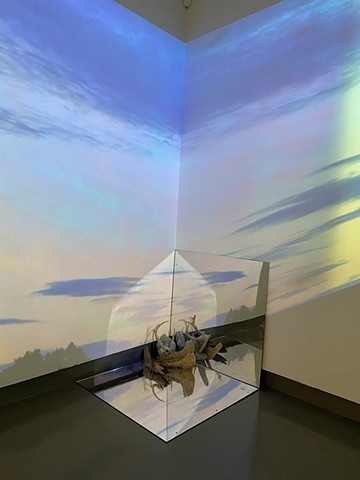

The pond and Arabia Mountain contain much of the aesthetic grit for Frey’s current artistic practice. She responds intuitively to the material triad of dry, hot granite, the reflective surface of water, and the soft, ephemeral touch of vegetation. Frey says in a statement about the work that, “Organic elements are interrupted by hard angles - real space is juxtaposed with the illusory.”

Frey plugs into the sublime by making temporary marks in spaces that are defined by the immensity of geologic time. The work is not so much a making of objects as it is a series of actions and commingling of materials. She creates patterns with available rubble, ingredients that are the detritus of the quarrying industry and millions of years of erosion. She pairs manufactured materials such as dichroic glass, mirrors, and metallic fabrics with fragile blooms and chunks of wood in impermanent arrangements.

Her outdoor projects can be understood as an unfolding process. The first phase is her observation of the site over time - she makes multiple visits in different seasons - followed by the repetitive activity of her labors, such as raking, hauling, and placing. Frey says that people generally don’t disturb her compositions, so she returns multiple times in a process that can last days or weeks.

The illusion of human separation from nature is fractured by Frey’s concoction of mirrors, light, and air. Reflected planes disrupt the field of vision and suggest a process of transformation aided by divine flashes of sunlight. The transience of the work lends it a magical quality. Her gestural elaborations can be imagined as radiant sutures connecting our fleshy, fragile selves with immortal stone and light.